Science

Frogs and Toads Together: Why do Amphibians Group Up?April 11, 2025

1

If you’ve considered adding a learning garden to your school’s outdoor space, but you’re not sure the logistics to make it happen or where to find garden grants to help you fund the project, this is the article for you!

I had the opportunity to interview Jeanne Henderson, former president of the Wild Ones Mid-Mitten Chapter and former naturalist at Chippewa Nature Center, about this topic. In her position with Wild Ones, she was provided regular communication on a variety of garden grants and she had the opportunity to work with teachers on grants for learning gardens in their space.

Given her extensive experience with garden grants, creating pollinator gardens, and vast plant knowledge, I trusted her to give us the goods to help teachers make progress toward a learning garden in their outdoor school space.

Don’t need all the info? Use this list to skip to what you need:

Where to look for garden grants

When to look for garden grants

What to include in your grant proposal

Gardens are amazing outdoor labs and provide many benefits to student learning (if you want to hear more about those benefits, check out episode 8 of the Naturally Teaching Elementary Science podcast where I interview Victoria Hackett about learning gardens). But if you’re ready to go all in, Jeanne and I are here to help you find garden grants to fund your learning garden, give you suggestions on what to include in your grant proposal, and help you plan your space (I say “we”, but really, Jeanne did all the work!).

Jeanne offers a ton of information for this question, including a shout out to Wild Ones, a national organization whose mission is “connecting people and native plants for a healthy planet.” Jeanne was formerly on the board of the Mid-Mitten Chapter and has been a longtime member, giving her confidence in this organization as a great place to seek funding for your learning garden.

She says, “Wild Ones has offered SEEDS FOR EDUCATION grants for many years…There are 91 chapters and 30 seedling (new chapters) in 34 states, so there may be a chapter nearby from which teachers can partner and receive advice. If there is not a local chapter, teachers can still apply.”

Applications for the Wild Ones Seeds for Education grants are considered by this criteria:

Jeanne points out that “[t]hese criteria ensure that funded projects are impactful, sustainable, and aligned with Wild Ones’ mission. The most important factor is the long-term educational value of each project.”

Another option for funding is a Michigan organization, but can inspire your research for funding in your state. The Wildflower Association of Michigan considers projects that:

If you’re looking for some learning gardens inspiration, check out the pictures on both the Wild Ones and Wildflower Association of Michigan websites; there are great shots of students in action developing their outdoor space with grant money.

I also found that Seed Your Future has a fantastic ongoing list of grants for edible gardens. Growing Spaces also has a few options for schools across the United States; they even have suggestions for community gardens if you wanted to turn your gardening project into a service project with your students. National Agriculture in the Classroom also keeps a running list of garden grants…there are so many organizations willing to help teachers put together gardens, you’re clearly onto something big here!

Finding the grants is only part of the battle, but you’ll get the most success when you do that research during typical application periods. Jeanne says, that “…most applications can be written and filed in the fall semester, with awards given in the next spring.”

With that information, from the release of this article, now is a good time to start looking for local and state garden grants that you could apply for. If you’re reading this article after July 2024, it appears as though many grants open their submission periods towards the end of summer through the end of fall.

As an example, the 2025 Wild Ones Seeds for Education submission period is from July 14th-November 15th, 2024 and the awards are expected to be given by February 15th, 2025. Likewise, the 2025 Wildflower Association of Michigan submission period is from July 31st-December 1st, 2024.

It’s also important to note that this process takes a lot of planning and won’t happen overnight. Make sure to map out your timeline, gather all the necessary materials, volunteers, and information to make your project as seamless and enjoyable as possible (and make sure to include your students in as many parts of that process as possible!)

Jeanne has had the opportunity to help implement as well as select garden grants in her roles with the Wild Ones and at the Chippewa Nature Center. She offers the following advice for important topics to include in your grant proposals: “Teachers should describe exactly how and why they will use the garden, across all subjects and grades (if intended). If they have a specific theme or purpose, such as a pollinator garden, rain garden, shade/woodland garden, they should explain this also.”

She goes on to include that, “[i]f awards are designated for native plants and seeds only, then the teachers will have to get additional funding from other sources for things such as soil tests, mulch, fencing, tools, or site preparation.” It’s important to read the criteria for each grant closely to determine what would be covered if you were awarded money and include descriptions for what you need to make your learning gardens happen.

Aside from grants, you can also reach out to local gardening stores, hardware stores, some pet stores, and even dollar stores to see if they have anything they’d be willing to donate to your project (or better yet, have your students write letters about your project to these organizations).

If you have storage space, I’ve found success reaching out to stores at the end of summer and the beginning of fall when they’re switching their seasonal goods from gardening supplies to holiday decorations. Oftentimes there are leftover watering cans, gardening gloves, loose tools, and more that the store can write off if donated. I have purchased a lot of quality spades from the Dollar Tree in my town that are durable metal and have withstood the power of children for years; you just never know where you’ll find treasures for your project!

So where should you begin with the planning of your learning garden? Jeanne offers us some great insight and advice. She says, “[m]ost important is the site preparation, overall design, and maintenance plan. Get permission from the principal and the cooperation of the school’s maintenance staff to ensure that the garden won’t disappear over the summer.”

Buy-in is critical for these learning gardens to be successful; Jeanne speaks from experience that you want to make sure that ALL administration and maintenance staff are on-board, otherwise you can lose your hard work and outdoor lab with one quick swipe of a lawnmower.

Jeanne gives us the following advice for site prep:

With her love of all things plants, Jeanne gives us some advice about using native plants for your learning gardens. She suggests to “…[l]earn about the native plant species before you make selections [of plants] to order. The local Wild Ones chapter can help you with this, or a local garden club, or local community college biologists, or local landscape companies who have experience using native species.”

Jeanne is very passionate about using native plant species because they come with tremendous benefits for both your students and your local plants and wildlife. Over the years, I’ve learned from her that native plants can:

It’s also important to keep in mind that some garden grants will only allow you to purchase native plants so it’s worth doing your research and selecting plants that will work for your soil type, the amount of sunlight your space has, and can be managed with the amount of water you have to work with.

Jeanne encourages teachers to consider “…[including] more plants that will bloom in spring and fall since that’s when school is in session, offering more opportunities to use the outdoor space…Use the scientific names to research plants and when ordering – [do] not rely on common names because they are not the same across geographic areas, and some plants have more than one common [name],”

Jeanne even gave us some great insight on where you can research plants for your learning gardens:

She also suggests checking out the Schoolyard Habitat program guide to create a habitat garden from the National Wildlife Federation. And in her very thorough fashion, she gave us two locations that you can look up native plant nurseries:

Don’t forget to think through how you plan to care for your learning garden so that you can include your maintenance plan in your grant proposals. Jeanne reminds us that “[f]inding people to help with planning, site prep, and maintenance is extremely important too. Including students in as many steps as possible is the goal.

“Enlist the help of families of students who will help maintain (weed and water) the garden over the months when school is not in session. This is very important for the first year while the plants are getting established. Volunteer weeding events over the summer can bring families and education staff together, building community and sharing knowledge.”

I asked Jeanne to share her experience working with a local school to plan, prep, and plant a pollinator garden in their greenspace. She recounted, “[a] teacher at a local elementary school asked for help from the Chippewa Nature Center (CNC) and I responded, as I was an interpretive naturalist there. She showed me the area selected and we measured the size.

“She got a soil sample tested by the state Cooperative Extension Service, and said the students wanted to grow a pollinator garden. The students were already involved in outdoor lessons since they had a woods and a small pond on the property.

“I developed a list of full sun to part sun plants that I knew would grow, and the teachers with their students selected which ones they wanted to purchase. Together we made a diagram of how the plants would be spaced, the number of each species, and grouped by height, color, and bloom times.

“The teachers purchased the plants at the CNC Native Plant Sale in late May and put them in the ground about a week later. The students placed some mulch around each plant plug, though not all the ground was covered between plants (not enough mulch).

“The first summer, teachers and school maintenance staff kept the plants watered. I checked on it a few times and about ¾ of the plants grew well. Students created labels for the plants and the teacher put a decorative fence around the space.”

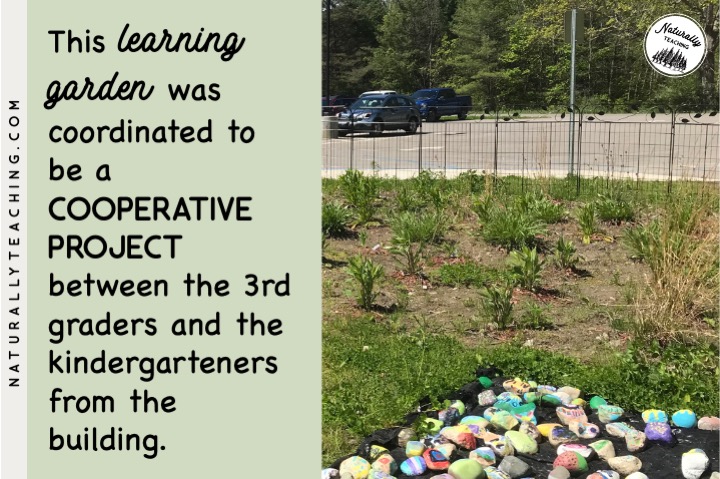

I was there the day that Jeanne worked with the students to plant the garden and she coordinated it so that it was a cooperative project between the 3rd graders and the kindergarteners from the building. The 3rd graders were in charge of reading the plant labels and using the diagrammed plan to find where the plants were meant to be planted. The kindergarteners were in charge of digging holes and planting the plants with the help of the 3rd graders.

It was a wonderful experience watching the kids’ energy as they worked together to create their outdoor lab; they really took ownership of the space. It was a slightly chaotic event, but the chaos was electric and inspiring. I spent a lot of my time handing plants to 3rd graders but I made sure to listen in on the conversations of the 3rd graders with their kindergarteners and they were all so excited about what was transpiring.

While it lasted, this pollinator garden served as an outdoor lab to observe insects up close, pollination in progress, plant heredity, food chain investigations, seed dispersal, and so much more. Unfortunately, the second year of its existence, one of the school maintenance staff eliminated the garden because they didn’t know what it was or what it was used for – this is your reminder to make sure ALL maintenance staff know what your space is or you install fencing that can’t easily be removed.

So as you look for ways to fund your learning garden, make sure to look for garden grants. There are lots of organizations that want to help schools get gardens installed in school yards. Remember Jeanne’s advice and really think through your site preparation, your design, and your maintenance plan.

Hopefully this interview got you thinking about how you could get a learning garden at your school. If you need some help convincing admin or you just want more information about the benefits of learning gardens, check out episode 8 of the Naturally Teaching Elementary Science podcast!

A huge thank you to Jeanne for her time and insight. I truly appreciate all of her knowledge and experience; hopefully you found it helpful too!

Jeanne Henderson worked for 29 years at Chippewa Nature Center in Midland as an environmental educator and interpretive naturalist. She taught many school programs, family public programs, led field trips, and wrote nature articles. She was in charge of the annual native plant sale for 6 years, ordering plants and helping people learn about each species, so they could make good selections. She graduated from Central Michigan University with a B.S. in biology and conservation. Jeanne’s 18 year membership in the Wild Ones Mid-Mitten Chapter continues to help her grow in knowledge about native plants, invasive plants, insects, birds, and other vertebrates. She enjoys identifying plants and visiting nature preserves, gardens, and wildlife areas.

Feeling inspired to find garden grants for your outdoor space? Share your thoughts in the comments section.

Check out this podcast episode to hear more about learning gardens with guest Victoria Hackett!

One thought on “Garden Grants and Plans: Where to Look for Funding and How to Prepare for Success”